We know that the Bible is both the most controversial and most popular book of all time. It was the first to be printed on Guetenburg’s printing press. Its sales have far surpassed any other book. It’s also the one that people choose to burn, to put down, and to cast doubt upon.

At one point in America’s history, it could be said that the Bible– particularly the King James Version– permeated the culture to the point that you were uneducated if you did not know portions of it:

Americans at the time mostly agreed with these sentiments, because the impact of the KJV was everywhere so obvious. It was obvious for business, with major firms like Harper & Brothers having risen to prominence on the back of its Bible publishing. It was obvious in the physical landscape and in many households because of the widespread use of Bible names for American places (95 variations on Salem) and the nation’s children (John, James, Sarah, Rebecca). It was obvious in literature, as with the memorable opening of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick: “Call me Ishmael.” And it was obvious in politics, with no occasion more memorable than March 4, 1865, when four quotations from the KJV framed Abraham Lincoln’s incomparable Second Inaugural Address: Genesis 3:19 (“wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces”); Matthew 18:7 (“woe unto the world because of offences!”); Matthew 7:1 (“judge not that we be not judged”); and Psalm 19:9 (“the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether”).

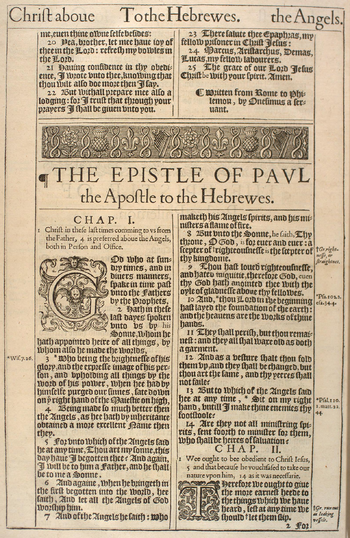

Because the KJV was so widely read for religious purposes, it had also become a source of public ideals. Because it was so central in the churches, and because the churches were so central to the culture, the KJV functioned also as a common reservoir for the language. Hundreds of phrases (clear as crystal, powers that be, root of the matter, a perfect Babel, two-edged sword) and thousands of words (arguments, city, conflict, humanity, legacy, network, voiceless, zeal) were in the common speech because they had first been in this translation. Or to be more precise, because they had been in the KJV or in the earlier translations, like those of John Wycliffe’s followers (1390s) and William Tyndale (1520s), that King James’ translators mined for their own version.

But things have changed from those days. For one thing, the Bible is no longer considered a guiding influence to our culture. In this day of multiculturalism and tolerance (to the point of exalting other religions I would suggest) we have removed it from public discussion. It’s fine for “God” (whoever that may be) to bless America, and for generic prayers to be made to “Him” (or maybe “Her”?), but it is we the people that know what’s best for America, and let’s keep God where He belongs– in the churches and houses.

Another thing has changed, and I’m just now mulling its influence. We now have more versions of the Bible than at any time in history. We have multiple versions in English– from KJV, NKJV, NASB, NIV, NIrV, and the list goes on. We have versions in Klingon and other forms of created languages. In creating all of these translations we have lost something. Not meaning– for I believe that there are some good translations that help us understand what the original text meant better than trying to remember that the KJV word “conversation” means “manner of life” in today’s language.

What has happened is that we no longer have a base text– something that everyone refers too. In one of the most popular verses in the New Testament, John 3:16, some people know it as saying that God sent His only begotten Son, and others now have read it for the first time as saying His one and only Son. Phrases in their grand and glorious King James English wording have now been supplanted as new generations pick and choose a translation that best suits them.

I’m not even suggesting that we all go back to using the KJV only. I’m definitely not of that stripe. What I am suggesting is that we are now realizing the effect of multiple translations in a world that used to have one and wondering about the long term effects.

I hear you on the John 3:16 passage…take Awana for instance. My girls have been in two different Awana programs, one before our own church began it and that one used KJV handbooks. Our church uses NASB I think. At any rate, it’s annoying to me to have my oldest know KJV and my middle learning NASB. The oldest can only help the youngest when the handbook is in front of her.

Just a little peeve.

I’ve never thought very deeply about the multiple versions out there, I was just glad we had more than KJV to go on…you make some very good points.

I sometimes wonder if we would all be better off learning Hebrew, Greek and Aramaic!

There is a big difference between what begotten and one and only means. BEGOTTEN implies flesh of flesh, one and only not so much… Too many differences for me. I think I will stick with KJV. THough occassionally I will scan other versions as MIN mentioned for added context, but seems to me most newer versions make the words mean less and less as opposed to more and more.

Mrs Meg Logan

I’m not sure we need Aramaic. There are only a few words of Aramaic in the Bible, but there would be a lot of mileage in learning Hebrew and Greek. Unfortunately we are not quite sure about the cadence of Koine Greek, which is why the rules of accents are really completely superfluous.

Hebrew is a fun language, but extremely difficult. The Greek alphabet is easier to learn than Hebrew, which has lots of graphemes that look very similar to one another, and Greek is an indo-european language which shares grammar and root words with English and other indo-european languages. Semitic languages are very different, with some quite remarkable grammar!

However, the Jews teach Hebrew to their children. Maybe Christians should teach Hebrew and Greek to our children.

That’s quite the idea, Stephen. I know that I’ve read where Vox Day has talked about training children in Greek at a young age when they can grasp a lot of things in a short time. I’ve actually wondered about teaching all languages a whole lot younger than the schools do.

Yes, children under the age of about 5 learn language in a completely different way to older children, and tend to produce much better accents when they learn young. My nephew has a wonderful French accent.

Here in Wales we have a fully bilingual community, so children can be immersed in Welsh from nursery onwards. This works very well, but when it comes to reading, you need to make a choice. Because rules of pronounciation differ markedly between the languages, the child has to learn to read priomarily in just one language. Welsh medium schools do not tend to teach any English reading to children until they are seven.

As Koine Greek is primarily a written language (with its own alphabet) I don’t think we need to teach it too young. I do think there are distinct benefits to learning a second language early though – because it aids in acquisition of further languages.